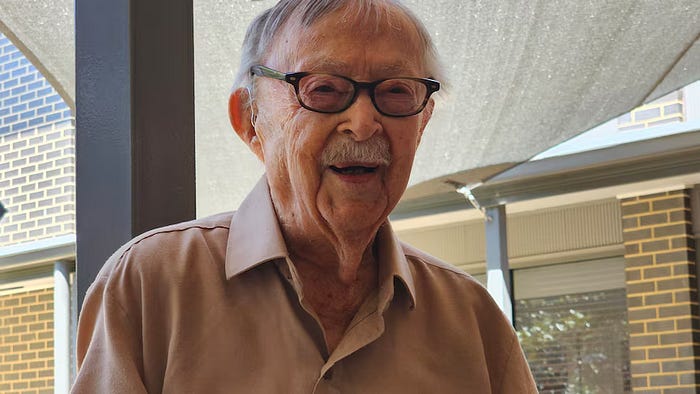

Ken Weeks is the oldest Australian man on record. Weeks recently celebrated his 112th birthday. He was born on October 5, 1913.

People today are living longer than their parents or grandparents ever dreamed.

We are living through a quiet revolution, one that previous generations could only dream of. Thanks to advances in medicine and wellness, living into our 80s, 90s, and even beyond is no longer an exception but an emerging rule.

This gift of time, an extra 20 to 30 years of life, should be a cause for universal celebration.

Unfortunately, a troubling paradox is emerging. We’ve reached the goal of longer lives, but we haven’t given people the map to navigate this new, extended life journey.

The evidence shows a quiet yet concerning increase in feelings of despair and, sadly, in suicide rates among people in the 50-plus age group.

The old idea of “retirement” is failing us, and it’s time we built a new one.

The Changing Landscape of Aging

The Hidden Triggers

The suicide rate is increasing among those over 50, and it’s not caused by just one reason. Instead, various stresses often build up until someone feels overwhelmed.

Why?

Identity & Purpose Loss

Work provides structure, roles, respect, and meaning. When it ends or undergoes a deep transition, many find it hard to replace these. Without careful planning, the distance can appear wide. Some people only realise too late that they lack passions, projects, or community ties outside of their job.

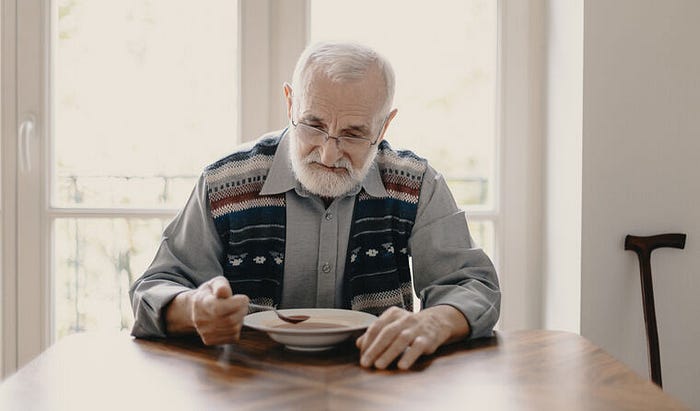

Isolation and Shrinking Social Ties

After 50, friendships tend to decline as children move out, spouses pass away, or health and transport issues make outings challenging. Social circles formed through work or parenting may also shrink, leading to constant loneliness.

Health Decline and Chronic Illness

As people age, they face a greater risk of chronic pain, disability, sensory impairments, and cognitive issues. Managing these health conditions and functional limitations can impact a person’s dignity, independence, and happiness. This daily struggle of illness management can also test resilience.

Loss and Grief

Older people often face repeated losses: friends, siblings, spouses, roles, and abilities — grief builds up. In many cases, they feel they are losing more than they are gaining.

Financial Stress and Insecurity

Even disciplined savers may find their resources stretched by longer lifespans, healthcare costs, or underestimating their longevity. Economic pressures can lead to anxiety, shame, and hopelessness

Underdiagnosed Mental Health Conditions

Depression in older adults is often overlooked or dismissed as “just part of getting older,” which it is not. Older people are less likely to get help or reveal emotional struggles.

Cultural Blind Spots and Stigma

Society itself sometimes reinforces negative stereotypes about aging. The belief that “older people are less valuable” quietly seeps in, whether through media images or workplace practices. These social cues can make it harder for people to make contact, feel heard, or seek help, making struggles more invisible.

While everyone’s journey is special, these triggers remind us why it’s so important to prepare not just financially but also emotionally for aging. Facing these feelings alone or thinking, “this is just how aging feels,” can be the biggest risk.

Why This Looks Different from Previous Generations

In past generations, people generally did not live as long after retiring. Their social identity and role change happened over shorter periods. Also, extended families often lived closer together, and local community networks were stronger.

Today’s mobility, fragmented families, shifting career standards, and rapid cultural changes leave many over 50 feeling lost with fewer anchors.

These hidden triggers interact in unpredictable ways. If any of these factors are left unaddressed, a person feels increasingly vulnerable.

The Way Forward: Six Ways to Build Your New Life

Given these challenges, how can you prepare for a longer and more meaningful life after 50?

- Cultivate a Mindset of Curiosity:

The single most important skill for this new chapter is adaptability.

The world will not stop changing, and neither should you. Be curious. Learn a new language, figure out how to use that new app, take an online course on a topic you know nothing about.

An open and curious mind sees this stage not as a slow decline, but as an unprecedented opportunity for growth. You have the wisdom of experience and the gift of time. It’s a powerful combination.

Never stop challenging yourself.

2. Redefine Purpose and Structure:

Instead of just drifting along, create new routines that bring more entertainment and purpose to your day.

Filling your daily schedule with goals, social activities, exercise, and hobbies can make you feel a positive sense of progress and achievement.

3. Redesign Your Social Network:

Your social well-being is now a project you need to actively manage.

Don’t wait for the phone to ring.

Arrange regular catch-ups with friends and family. Join clubs that match your interests, whether it’s bushwalking, reading, or chess.

Look for intergenerational opportunities, like volunteering at a school or community centre.

A thriving social life includes both deep connections and casual acquaintances.

4. Reassess Financial Planning Through a New Lens:

A 25-year retirement requires a different financial plan than a 10-year one.

The fear of the unknown is a major source of anxiety. Confront it directly.

Meet with a financial advisor specialising in longevity planning. Gaining clarity on your financial situation, even if it’s not perfect, restores a sense of control.

5. Protect Emotional Health:

Your health supports your independence. Understand the difference between everyday sadness and depression.

Imagine a therapist as your friendly “mental fitness coach’ who can help guide you through your emotional changes.

You have a mind-body connection. Prioritise exercise for its benefits on how you feel and what it allows you to do. A daily walk, swimming, or yoga can all boost your mood, support your mobility, and help you stay connected with the world.

6. Apply Protective Factors:

Research has identified several protective strategies that help prevent suicide in older adults.

These include:

- Feeling connected to others

- Having a sense of belonging

- Being able to openly discuss death

- Possessing coping strategies

- Exploring spirituality or life philosophy

- Feeling a sense of control

These steps are not guarantees, but they shift the odds.

Life after 50 is not a final chapter. It’s an invitation to learn, grow, and connect in ways never imagined before. The power of purpose, relationships, and adaptability — not just money — makes this stage rewarding. When people and communities welcome change together, life gets brighter as you age.

Retirement is not a “retreat” from life but a chance to create deeper meaning.

Sources:

- National Council on Aging, “Suicide and Older Adults: What You Should Know,” Jan 2025

- Harvard Health, “If you are happy and you know it…you may live longer,” Oct 2019

- “Happy people live longer because they are healthy people,” PMC, July 2023

- SuicidePreventionAust.org, “Stats & Facts,” Oct 2024

- RACGP, “Suicide rates reveal the silent suffering of Australia’s older people,” Aug 2022

- “Adjusting to Retirement: Handling Depression and Stress,” HelpGuide, Aug 2024

- “7 Ways To Mentally Prepare For Retirement,” ARWM.com.au, Oct 2023

- “How to Assess if You’re Mentally Prepared for Retirement,” June 2025

- “How to prepare emotionally for retirement,” AgeUK.org.uk, Feb 2025

- “Late-life suicide in an aging world,” Nature, Jan 2022

- “The Retirement Process: A Psychological and Emotional Journey,” University of Washington, July 2023

- “Suicidal behaviour in older age: A systematic review of risk factors”

- “A narrative review: suicide and suicidal behaviour in older adults”

- “Protective factors against suicide among older adults”

- “Suicide and self-harm among older Australians”

- “Advances in our understanding of how to prevent suicide in older men”

- “Suicide and Older Adults: The Role of Risk and Protective Factors”

- “A systematic review of psychosocial protective factors against suicide”

- “Suicide and self-harm in older adults”